Stretchable “e-skin” may be able to reconstruct touch

Touch is a sense we often take for granted. We discuss blindness and hearing loss in medicine. We certainly have discussed the loss of taste or smell a lot during 2020.

However, unless you’ve had a limb amputated—or lost your feeling in a limb for some other health reason—you likely can’t imagine not being able to feel something with your largest organ: your skin.

That’s part of why the technological recreation of touch is so exciting: It’s part of our everyday lives, so losing it can be devastating for patients. Another reason is that the experience of touch is incredibly complex to try to recreate.

Yet, a new soft electronic skin (e-skin) system developed by Stanford researchers may reconstruct not just the appearance of skin—but also that nerve response we perceive as touch. The research team successfully tested the material on a rat, with different pressures applied to the sensor on the e-skin triggering nerve cells to fire in the rat’s brain.

In the same edition of Science, a team from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne published a paper about their own e-skin development, which allowed human amputees to feel the sensation of variable temperatures in their phantom limbs.

To explore the significance of these mind-blowing developments in e-skin technology, let’s dive into the landscape of this product—including its history and its possible clinical future.

This is not the first e-skin researchers have developed

This is the latest in a series of designs and developments tracing back to the mid-twentieth century.

In the early 1950s, researchers pursued the question of whether phantom limb pain could be used to control motorized prostheses, in an early version of the human-machine interfaces we see today. A decade later, “artificial touch sense” was introduced to prostheses with the help of pressure transducers calibrated to generate stimuli.

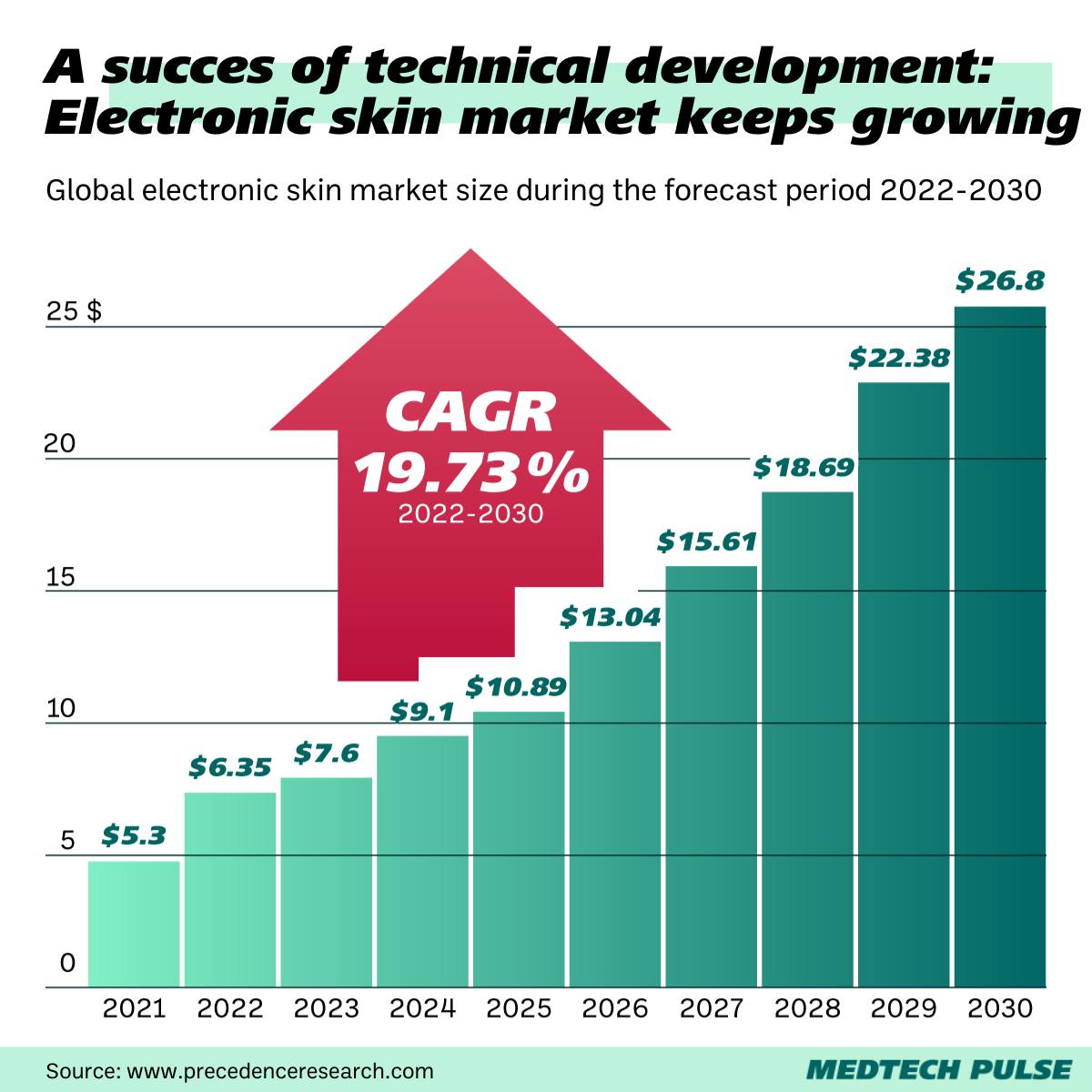

But the concept of robotic skins for the generation of touch stimuli took of in the 1980s. And the technological development of flexible polymers and large surface flexible circuits paved the way to the technology we’re discussing today. And the technology—and respective market—is only expected to keep growing in the next decade.

Surveying the landscape of e-skin products currently in development, we can see there’s a wide variety of materials-based approaches. Some researchers are starting with hard, inorganic materials and making them flexible. Others use soft, organic materials to ensure the device is flexible from the start.

The clinical applications of e-skin also abound with possibilities. A team from MIT, for example, is exploring the use of e-skin as a wearable sensor for remote health monitoring. This device harnessed the power of crystalline gallium nitride and the conducting properties of gold to boost incoming and outgoing electrical signals. It was sensitive enough to pick up a heartbeat or even the saline level of sweat. Without requiring a chip, this device also makes a great candidate for a device that foregoes reliance on microchips—the supply chain of which has given our industry a headache recently.

The future of e-skin

Despite these varying potential applications of e-skin technology, a clinical reality is still far away.

“You can validate proof of concept into animal models, but that doesn’t mean it’s going to be implemented very quickly in humans,” said Stéphanie Lacour, a neuroengineer working on stretchable biomaterials at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology.

Right now, most e-skin researchers’ goals are to prove that it’s possible to build this skin-like sensing system at all. Plus, demonstrating that their effective use is safe enough to try on humans. This step has taken decades.

Other researchers have been pointing out that the further development of biocompatible materials will be essential to making e-skin products useful beyond limited experimentation.

“The defense and rejection reactions of living tissues are extremely delicate, and as yet, the long-term stability of the interface between engineered materials and living tissues is far from satisfactory,” explained Tsuyoshi Sekitani, an engineer at Osaka University.

As we let researchers continue building on these incredible advances, we can dream of a future when prosthetics possess the ability to give patients the gift of touch.

Certainly, human-machine interfaces with complex (and even quite invasive) mechanisms have been growing in viability. Take the brain-computer interface, for example. Neuralink has just received its long-awaited FDA approval to begin human trials. Brain-controlled wheelchairs are successfully helping quadriplegic subjects navigate obstacle-filled rooms.

For this technology, the road to clinical viability may still be long, but we’re optimistic. A future with e-skin that reconstructs touch may not be as far off as we think.