From Brave New World to human trials: Progress in artificial wombs

Artificial wombs aren’t a new idea. But giving this technology a human clinical trial has seemed like a far-off fantasy.

That is, until now.

The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) has a team working on a bag filled with artificial amniotic fluid that kept a baby lamb alive for four weeks in 2017. They’ve since tested the device on pigs and have founded the startup Vitara Biomedical.

They’re not the only team in the race, but they’re by far the closest to human trials.

Today, we’re diving into how this technology works, the purposes it does (and doesn’t) serve, and the abundant ethical dilemmas it raises.

The teams leading the artificial womb race

According to a 2022 presentation by team leader Alan Flake, CHOP’s “Biobag” has gotten Vitara breakthrough therapy status designation from the FDA.

Another contender in the artificial womb space is a team from the University of Michigan—which takes a bit of a different approach. This team’s artificial placenta is the centerpiece of a pump system rather than a fluid-filled bag.

George Mychaliska, a pediatric surgeon leading the Michigan team, pointed out that their goal is to update the current standard of care for very premature babies, stretching their maturation timeline until they’re ready for the more sophisticated life support systems available to them in NICUs.

Another team from the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto is working on an artificial womb using pig fetuses but has not had luck supporting them for longer than a day or so.

Dystopian tech or patient need?

Readers of Aldous Huxley’s might be alarmed by this news, imagining the replacement of human parents by artificial wombs.

And of course, pairing artificial wombs with IVF is a time-tested approach to imagining reproduction sans traditional pregnancy.

But if you’re reading closely, you’re probably noticing that this isn’t quite what teams working on this tech have in mind.

The use case for these artificial wombs would be extremely premature babies—infants born at less than 28 weeks’ gestation. These babies rarely survive long after birth.

But isn’t birth that early very rare? Yes and no.

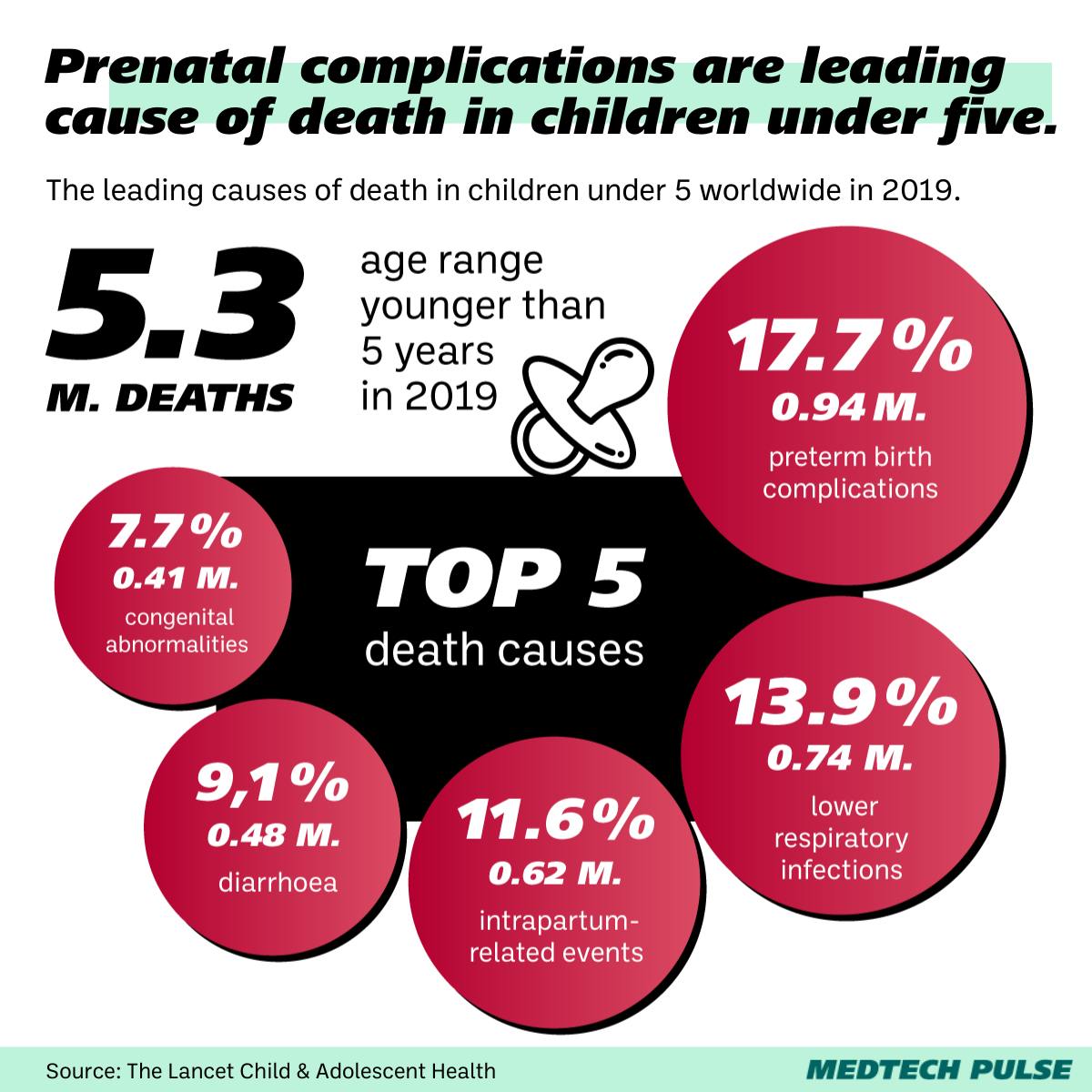

In the US, about 10% of births are premature (and this rate is higher among Black mothers). Worldwide, complications associated with preterm birth lead to staggering amounts of deaths.

While extremely premature babies account for less than 2% of premature births, about half of these babies currently don’t make it. And of the ones that do, 1 in 5 develop severe neurodevelopmental issues by age 2.

And according to the U.S. CDC, the preterm birth rate appears to be growing.

These statistics are driving these innovations—to try to prevent unnecessary infant deaths and give them a chance at a healthier future.

But the devices are a new class of preventive health technology—which makes them both exciting and very challenging to study.

Next steps: Answering ethical questions

One of the biggest signals that work on artificial wombs is getting close is that the FDA is taking it seriously.

The agency convened a two-day panel meeting in September to discuss the animal data and ethical issues underlying this work.

One of the biggest issues is the question of moving to human trials. At the panel, even Flake acknowledged there is no ideal animal model that can assure researchers of how a human would fare in these conditions.

Another key question is around informed consent. Given how new this technology is, researchers, providers, and ethicists are needing to determine how this option will eventually be communicated to hopeful parents.

Bioethicist Chloe Romanis framed this question clearly: “How are we going to make sure that people have all of the information they need, and not in an emergency, in order to be able to make the decision?”

And then, there’s the broader cultural conversation. And no, we’re not talking about the science fiction one. Ethicists like Romanis have pointed out that this technology is likely to reframe how society and policymakers think about fetal viability—which is an ever-relevant issue when it comes to abortion restrictions.

“It seems intuitive that this vulnerable entity should have more rights and protections than a fetus, because it doesn’t impact pregnant people anymore,” Romanis said. “But also, there are still some quite difficult questions about whether we should treat it exactly the same as a baby in all circumstances.”

But before grappling with these broader questions, the FDA is focused on how to get this technology properly vetted. Namely: Do we need more animal models? And when we’re ready to move on to human trials—how?