3D-printed ear transplanted to first patient

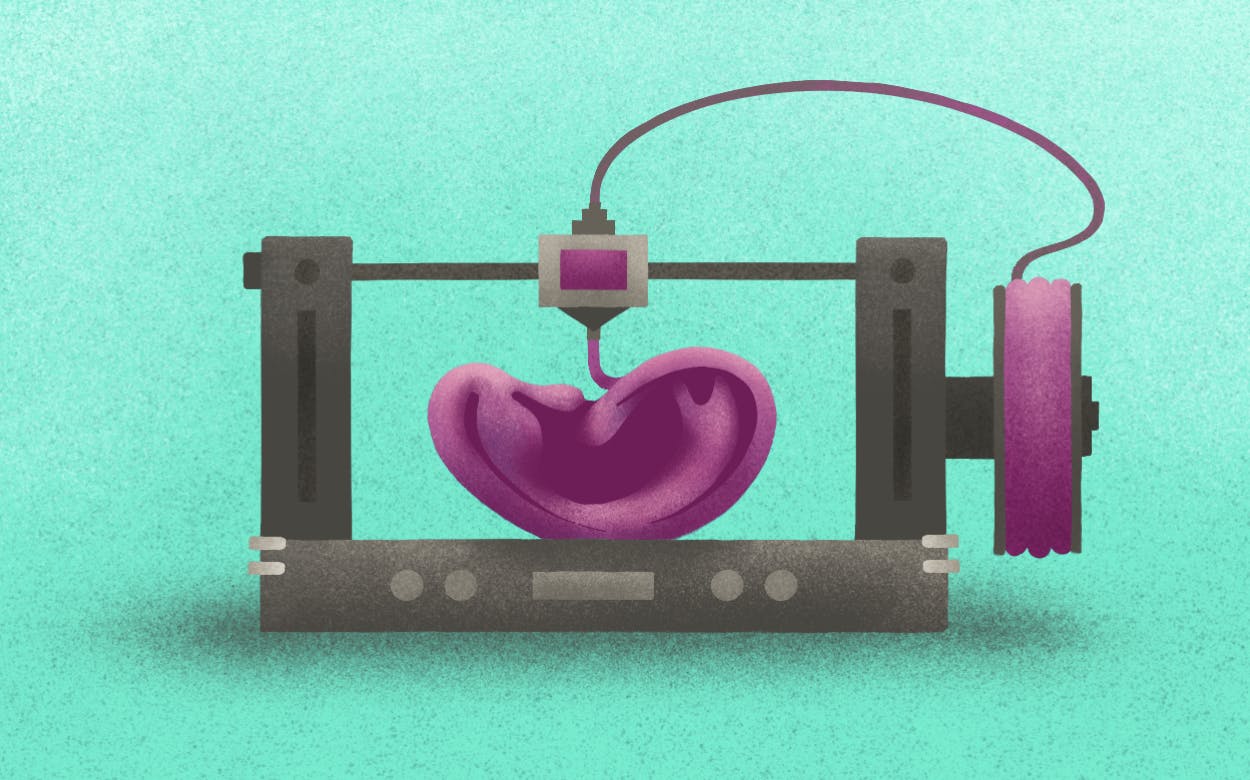

What if doctors could simply print organs instead of finding a matching donor and hoping the patient's body doesn't reject the transplants? Surgeons who transplanted a woman with a 3D-printed ear made from her own cells provided an answer to this question.

In late May 2022, a research team from the United States successfully transplanted a 3D-printed auricle. The recipient was a 20-year-old woman born with a rare auricular malformation.

The auricle was manufactured by 3DBio Therapeutics. The company extracted cartilage cells from the patient, propagated them in a special nutrient solution, and then mixed them with a special bio-ink. Afterward, a 3D bioprinter formed a replica of the auricular cartilage—based on a 3D scan of the patient's other healthy ear—within 10 minutes.

The transplant was part of the first clinical trial to study the safety, benefits, and applicability of the 3D implant. The operation marks the beginning of an approval process that requires at least 11 of these transplants to be performed in California and Texas.

Bioprinting will soon be a reality

The case of the 3D-printed ear follows a handful of other recent groundbreaking advances in transplant technology.

- Last fall, surgeons at NYU Langone Health connected the kidney of a genetically-modified pig to the bloodstream of a brain-dead woman for the first time.

- Earlier this year, a genetically-modified pig was transplanted into the body of a terminally ill 57-year-old, extending his life by about two months.

- In late April, a team led by Boston University announced that they had 3D-printed a tiny replica of a living heart chamber.

If science has its way, 3D-printed tissue could soon replace more than just missing ears, which consist exclusively of cartilage and skin. Work is also being done on organs like the liver, the kidneys, and even 3D-printed lungs or blood vessels.

Transplantation economics

These types of bioprinting promise revolutionary applications in all areas of regenerative and restorative medicine, as well as in cosmetic surgery and pharmacological research.

The reason that science is making so much progress is that there is a significant transplant supply gap. Only healthy transplants help, and even then, there is no guarantee that the recipient organism will accept the transplant without complications.

Not to be neglected in the innovation calculation are the immense treatment costs that come when no transplant is available:

- The costs associated with organ failure are very high. Hemodialysis care costs the Medicare system an average of $90,000 per patient annually in the United States, for a total of $28 billion.

- The average cost of a kidney transplant in 2020 was $442,500, according to a study published by the American Society of Nephrology. Retail 3D printers, meanwhile, cost anywhere from a few thousand dollars to $100,000, depending on the complexity.

It seems that now is the time to break new ground—not only in terms of impact, but also in terms of economics. This may be a harsh reality, but it’s the truth we’re living in.

The future is within reach

Either way, the future is within reach. Science is making rapid progress.

We are seeing more and more incremental improvements and world firsts in the field of bioprinting. Accordingly, we expect an increase in successful transfer cases from science to practice in the coming years.

Even though the subject remains complex, and even though it will be years before fully functional biologically-printed organs can be implanted in humans, the goal is clear:

There is no practical reason why someone who needs a transplant should not get one.

And this is a cause we should all join.